South Africa’s private power market continues to gain momentum, and this time, it’s being driven from the ground up. The National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) has registered 181 new generation facilities in the second quarter of the 2025/26 financial year, adding a combined 1,401 MW of capacity and drawing over R30 billion in investment.

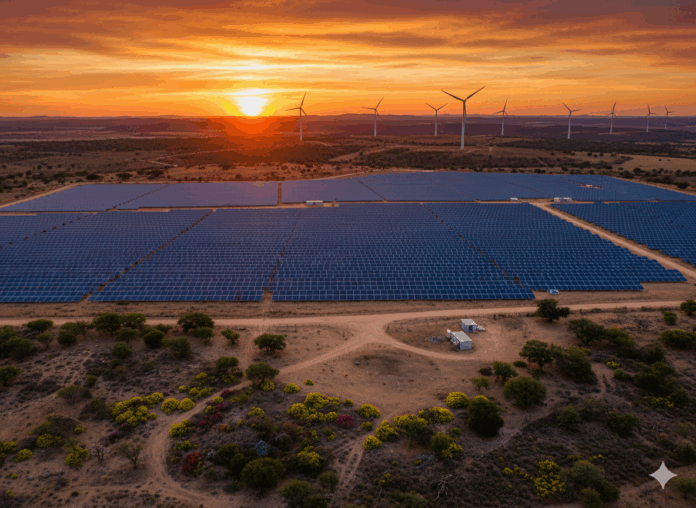

Nearly all of the newly registered projects (175 out of 181) are solar photovoltaic (PV) facilities. The rest include four wind projects, one biogas plant, and a single battery energy storage system. It’s a snapshot of how fast solar energy is dominating the investment pipeline, even as storage and alternative renewables remain marginal in scale.

The Western Cape emerged as the investment leader this quarter, accounting for over R20 billion and 872 MW of the total. Gauteng and Limpopo followed in the number of registered facilities, but much smaller in total value. In contrast, the Northern Cape, the leading renewable energy hub, ranked among the top three provinces in investment and installed capacity despite registering fewer projects.

Perhaps the most telling development lies in grid connection patterns. Of the 181 facilities, 88 are tied to Eskom’s transmission network, representing 1,326 MW of capacity and R29 billion in investment. The other 93, connected to municipal networks, contribute just 75 MW and R1.2 billion. The data reveals that large-scale generation is heading into the national grid, rather than local municipal systems still limited by distribution capacity and capital.

At an average cost of R21 970 per kilowatt, this wave of investment signals the scale of South Africa’s private-sector-led energy expansion. Since Nersa introduced the registration system in 2018, it has now recorded more than 2,236 facilities with a combined 16 GW of capacity, worth R328 billion. These projects represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the national power system, reshaping the energy mix without direct state procurement.

Nersa processed this quarter’s applications within an average of 10 working days, down from 12 days during the same quarter last year, when only 149 projects were approved. That improvement suggests the regulator is adapting to the flood of private investment unleashed after licensing thresholds were scrapped in 2021.

For industrial and commercial users, private distributed generation now offers a route to hedge against load-shedding, cut emissions, and decarbonise operations without waiting for new state-led capacity. For Eskom, it raises new questions about grid management, transmission access, and cost recovery as independent producers expand faster than the grid itself.

Yet, the shift also exposes uneven development. This is echoed by Dr Megan Cole of the University of Cape Town, in a 2025 study that highlights a “spatial and technical mismatch” in South Africa’s energy transition. Most utility-scale renewable projects are clustered in the southern provinces (such as the Western Cape, Northern Cape and parts of the Eastern Cape), while the coal-dependent towns and provinces in the north and east (notably in Mpumalanga, Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal) face the greatest risk of mine closure and economic disruption.

Meanwhile, the single registered battery energy storage system (BESS) in the 2nd quarter highlights how far the country still is from building the flexible infrastructure needed for a stable renewable base.

Nonetheless, a R30 billion investment for a new generation reflects how the private sector is now driving South Africa’s energy mix more than the public sector. As capacity builds across provinces, the next challenge lies in ensuring that regulations, tariff plans, grid expansion, and market systems keep up with the speed of decentralised power.