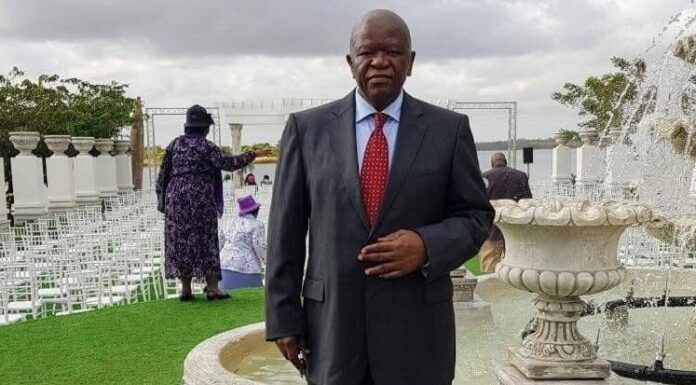

Veli Mahlangu, who passed away this past week, was a like younger brother to me, and a loyal comrade.

VS, as we affectionately called him, was humour personified. His humour broke deadlocks and brightened the sombre moments in our march to freedom.

A position of power never changed his view of the world. VS, a former Witbank Aces official, was comfortable in the boardroom, soccer changing room or under a tree in the sunny parts of Matjhiding. He saw value in everyone.

I will forever be in awe of his humility and ability to listen. He not only listened to those he agreed with.

Freedom fighter

His story is intricately weaved into the story of our freedom. Together, we mounted a spirited campaign against the imposition of independence in KwaNdebele, the broader struggle for freedom, and the transition to a free and democratic Soth Africa.

His story reads like a biography of a forgotten youth — a young person who fought for the freedom of the rural folk. The youth whose contributions are often relegated to footnotes of history, if recorded at all.

Today, the fight against the repressive KwaNdebele regime may seem insignificant. However, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report reminds us about missing persons, gruesome murders, torture, and detentions. Freedom was not free.

The reality, then, that choosing to fight for freedom was also tantamount to putting your name on the list of apartheid death squads did not deter VS. He raised his hand.

At odds with Pretoria

Enraged by Pretoria’s planned forced removals, VS, myself, Prince Senzangakhona, Prince Nyumbabo, and the entirety of the court of His Majesty King Mabhoko II met to discuss our response.

VS presented a formidable case for resistance. He knocked on the open door. As the inner sanctum of the King, we were ready to fight Pretoria.

We mobilized. We resisted. We prevailed.

The Apartheid regime abandoned the idea of forcibly removing King Mabhoko II and his subjects.

Bantustan established

Instead, the Apartheid regime, together with elderly men, devised the idea of a KwaNdebele Bantustan around 1977.

Around 1985/1986, at Pretoria’s nudging, the KwaNdebele government decided to pursue independence. By then, this nonsensical policy had already been adopted by Transkei, Venda, Bophuthatswana, and the Ciskei.

VS and us formed a think-tank to oppose the Bantustan independence.

We worked tirelessly to organise the community, business people, professionals, and the youth to oppose independence.

We used popular protest, law, and every means available to oppose independence.

State-sanctioned killing machine

In retaliation, the KwaNdebele government formed a vigilante group called Imbokotho and the Green Beans which acted as the state’s assault wardens.

The P W Botha regime strengthened the KwaNdebele government with its own security apparatus. It unleashed the SAP, the SADF, and the Special Branch on us.

Some of us were detained, displaced, imprisoned, and tortured. Others paid the ultimate price for our freedom.

The fight did not stop.

A civil war between the KwaNdebele government, Imbokotho, and the community intensified. More than 150 people died.

Properties owned by Imbokotho leaders and supporters were set alight.

We weakened Imbokotho. Its leaders fled the area but continued to make laws for us remotely and advanced plans for the Bantustan independence.

Women get the vote

We obtained a legal opinion stating that the Proclamation Constitution establishing the KwaNdebele government was unlawful because it denied women the right to vote and stand as candidates.

On the strength of this opinion, five women among our activists took the matter to the Supreme Court in Pretoria.

We succeeded.

The apartheid parliament revoked all legislative powers of KwaNdebele and then passed legislation that rectified all decisions taken by the KwaNdebele government, except for the decision to opt for the Bantustans’ independence.

In 1988, Pretoria called for a general election, with women entitled to vote.

At this stage, we decided to send a delegation to seek advice from the AÑC leadership in Lusaka.

We were advised to take part in the election to stop Pretoria’s surrogates from dominating the government machinery any longer. We were also briefed on SA’s path to freedom.

We established Intando Yesizwe to contest the election. Prince James was elected its president. I was elected his deputy, and VS became the treasurer.

We did not secure the majority in the KwaNdebele elections. We reported back to the ANC and sought further guidance.

Madiba’s orders

I vividly remember that during a briefing at Shell House, president Nelson Mandela tasked me with ensuring that Prince James became the Chief Minister of KwaNdebele. He emphasised that we should not let Pretoria control KwaNdebele.

A year later, I succeeded in my assignment. I became justice minister, and VS was appointed finance minister.

VS diligently looked after the public purse and jealously guarded it. He knew that we were there to transition our people to total freedom. He knew that controlling the KwaNdebele government in 1990 was key to the democratic project. It was not an end in itself.

Mandela’s instructions were clear. The structure of the negotiations process necessitated that the ANC controlled the KwaNdebele government. That is the role that we played.

When we delivered freedom, VS remained active in the ANC and in the formation of the new government.

When I was deployed as Mpumalanga’s Premier and elected the provincial chairperson of the ANC, I could rely on VS’s advice. We deployed him to be CEO of the Mpumalanga Agricultural Corporation. In this role, he worked tirelessly to promote food security and the development of black commercial farmers.

Today, SA is poorer for having lost a true servant of the people.

– Ndaweni Mahlangu was premier of Mpumalanga and mayor of Thembisile Hani district. He delivered a eulogy at Veli’s funeral.