With the South African universities racing against time to fulfill the government’s Language Policy Framework for Public Higher Education Institutions, linguistic experts say it will take many years for institutions to offer indigenous languages as a medium of instruction for academic programmes.

The policy, which is expected to kick off this year, aims to compel institutions to have at least two African languages as a medium of instruction for lectures, among other goals.

But the University of KwaZulu-Natal language, culture, and heritage expert Dr. Gugu Mazibuko said although the government was on the right track, there was still a long way to go, citing challenges in terminology development as one of the factors.

“The framework is essentially talking about multilingualism as a medium of instruction. While a few universities have made some notable strides, there is still a long way to go in terminology developments for a variety of study fields.

“Government should have made it compulsory for universities to conduct lectures in indigenous languages after attaining democracy and recognising 11 official languages.”

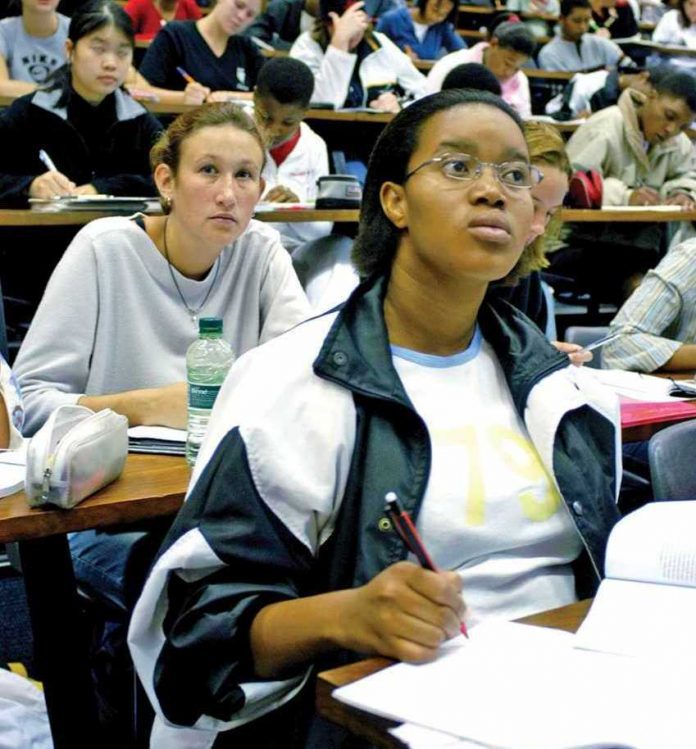

She noted that UKZN had recorded notable successes since introducing Zulu as a subject of choice in delivering lectures. “Students are divided into different groups according to their preferred language, either English or isiZulu.

“We have seen great academic progress in terms of students’ comprehension of their subjects and the overall pass rate.”

Mazibuko said higher education institutions should commit to and make clear language policies so that they are in line with the new framework.

“Multilingualism classrooms boost learning and decrease dropouts. A successful case is that of Cofimvaba schools where they decided that all their subjects from primary to high school will be offered in isiXhosa.

“This move paid dividends because the matric pass rate was increased for 2021. For many black students language is often a barrier to comprehension,” said Mazibuko.

The revised policy published in October 2020, makes it compulsory for academic institutions to develop languages that were historically marginalised. It is believed that the move will decolonise curriculums and level the playing field.

Professor Mpho Ngoepe, director at Unisa’s School of Arts pointed to several bottlenecks.

“The policy itself does not specify firm target dates. So, universities might not see this as an urgent or immediate need. It is necessary for the Department of Higher Education to issue a directive for individual institutions planning to include target dates for full implementation of the policy.

“This should be accompanied by funding to these institutions,” Ngoepe said.

“I think most students and even parents would prefer English as a language of instruction, scholarship, teaching, and learning.

“This is also compounded by the fact that at the elementary level from the fourth grade onwards learners are taught in English. As a result, later at high school, they are likely to struggle in reading and writing in an indigenous language despite being fluent in speaking the language.”

Follow @SundayWorldZA on Twitter and @sundayworldza on Instagram, or like our Facebook Page, Sunday World, by clicking here for the latest breaking news in South Africa. To Subscribe to Sunday World, click here.