It has been over six decades since the tragic Sharpeville massacre, but the area remains neglected – and hopeful.

The promises of a better life made at the inaugural ceremony of the Human Rights Day by the then president of the new democratic order Nelson Mandela in 1997 have yet to be fulfilled, while the unbearable conditions of Sharpeville continue to deteriorate.

On the same day and at the same ceremony, the country’s new constitution with its Bill of Rights were signed into law by Mandela – a momentous day on which a new dawn of democracy was unveiled to the people of Sharpeville and South Africa.

A visit by Sunday World this week ahead of Human Rights Day on Tuesday, uncovered a disheartening sight of a township plagued by massive potholes, dirt, overwhelming stench of dumps and crumbling infrastructure – and a sliver of hope.

The Sharpeville Library, post office, and Human Rights Precinct are all in disrepair, as are the lives of the people.

All things fall apart, as legendary author Chinua Achebe opined in one of his world-famous books. Things have fallen apart for the residents.

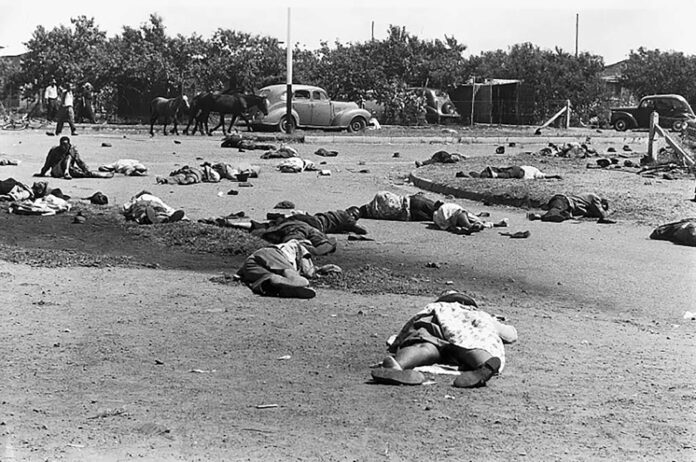

Tied by a blood-stained history, the people of Sharpeville today share the same sorrow: unfulfilled promises as was the case in 1960 when 69 peacefully protesting locals were mowed down by apartheid police for calling for a ban on pass laws.

For the Sharpeville residents, the “better life for all” promised by the governing ANC since 1994 at the onset of democracy remains a dream betrayed.

Locals battle for basic services such as safe drinking water, stable electricity supply, health services, refuse collection as well as the maintenance of recreational facilities. Rampant unemployment continues to plague the community, especially its younger generation.

Despite the international attention it garnered and the fall of apartheid, there is no end in sight to their suffering.

Themba Tau, 48, who runs a car wash in Pelindaba opposite the sewage and wastewater station on Seeiso Street, says Sharpeville’s living conditions are unbearable.

“The state of our township is deplorable – it’s dirty and not maintained. As you can see with people cutting grass, it’s almost the 21st of March, and that’s when politicians come around, but you will not find them here any other day. They make empty promises, but young people remain unemployed and idle.

“Tenders are awarded to the same people, leaving others with no opportunity. Nothing has changed since 1994. Our people have died in vain.”

The sewage and wastewater plant is dysfunctional. The area seems inactive except for the presence of two guards who are not protected from the pungent smell spewed from a highly polluted environment.

Historic buildings and sport facilities, once the pride of the township, have been vandalised. A hostel built during the apartheid era is now home to elderly people living in unhygienic conditions, along crumbling walls and illicit dumpsites. “They promised to build us better houses but to this day they still have not delivered on their promises. These hostel houses are too old; we fear that we will die before the government fulfils its promises to this community,” said a gogo who preferred anonymity.

Adjacent to the hostel, a school for pupils with disabilities is in a state of decay, with broken windows and overgrown grass. Close by lies a dilapidated structure originally meant to be a foundation phase school, which would have provided a lifeline to the many jobless teachers in the area. The building has become a white elephant.

“We had high hopes, but the individual awarded the tender for the project abandoned it.”

Crime in Sharpeville is rampant, a social ill exacerbated by extreme poverty and joblessness, according to Tau. “The community is facing a serious problem with drugs that are taking the lives of our youth, particularly in Pelindaba,” he said.

Lebohang Molebatsi and his father, who reside on Seilhatlole avenue, whose house is hanging by a thread owing to leaking water pipes that have not been attended to for several years, live without any hope that their lot will change.

Many houses along Seeiso Street and Seilhatlole Avenue are built on a wetland “and can collapse any day”.

The Molebatsi family remains hopeful. They think there could be light at the end of the tunnel. But doubt persists.

“We have noticed a pattern of councillors leaving their positions before any real help is provided. Meanwhile, our house continues to deteriorate, and although officials come to take photos, nothing happens. During rainy days, we are forced to squeeze into a small shack at the back of our property due to flooding. At this point we are willing to consider moving if that will help,” said Molebatsi.

Despite the challenges, there is a glimmer of hope. The police station where the Sharpeville massacre occurred has been transformed into the Kitso Information Development Centre, which encompasses an art and development centre.

Nicho Ntema and Terrence Tsoaela, who are some of the founding members, said the centre has had over 400 volunteers and employs 10 permanent staff since 2020. The centre provides a variety of services including life skills training, computer training, arts and crafts training, electric vehicle training, entrepreneurship training, enterprise development training and farming.

Said Ntema: “The centre serves as a beacon of hope for the community, providing a space to heal from the generational traumas and burdens caused by the aftermath of the massacre.

“As someone who personally experienced torture in the local police station, I can attest many people in Sharpeville grapple with the long-lasting effects of both the massacre and the apartheid regime.”

Dark clouds with a silver lining. That is what Sharpeville represents today.

Follow @SundayWorldZA on Twitter and @sundayworldza on Instagram, or like our Facebook Page, Sunday World, by clicking here for the latest breaking news in South Africa. To Subscribe to Sunday World, click here