I don’t know what those who’d met and been enthralled by the works of the late renowned Kenyan writer and scholar Ngugi wa Thiong’o will remember mostly about him. He died on May 28 in the US after a long illness. He was 87.

Like the throngs of enamoured readers worldwide who couldn’t get enough of his creative spirit, I mourn his passing.

In my head I’m playing the memory of our meeting in June 2017, when he was in this country, and I do not want it to fade. In fact, I just think it will stay with me for as long as I live.

Having made his name in English, he did an about-turn and started writing in his native tongue, Gikuyu.

It was his belief – an aha moment – that English was the tool of colonialists to subdue Black thought and aspirations, but in order “to decolonise the mind”, it was crucial for Africans to elevate their own languages.

By the early 1970s already, he had ditched his Christian name James and resorted to Ngugi [wa Thiong’o]. A man after my own heart!

One of my loudest laments is the current generation of our brood who are incapable of saying boo to a goose in their own home languages, not out of timidity but simply because they do not have the vocabulary.

What pierces my heart even more are the parents who hold it as a badge of honour that “my child cannot speak Sesotho”.

God help the Black man!

English is not a measure of wisdom, not by any stretch of the imagination. I’ve witnessed too many protest marches by the English in their homeland and read the gibberish on their posters to know my assertion to be true.

Pity this truth has not arrived at the doors of many homes in Kagiso, Kathorus, KwaZakhele, Kabokweni, Kwa¬kwatsi, etc.

Ngugi is gone to be with his gods, but his legacy endures.

Closer home I’m taken back to the writing of one Sabata-Mpho Mokae, who teaches creative writing at Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley, Northern Cape, but is currently on a sabbatical.

Like the elder statesman of modern African literature who has just departed, Mokae could easily have continued to write in English just to demonstrate that he was a “clever Black”, but he did not.

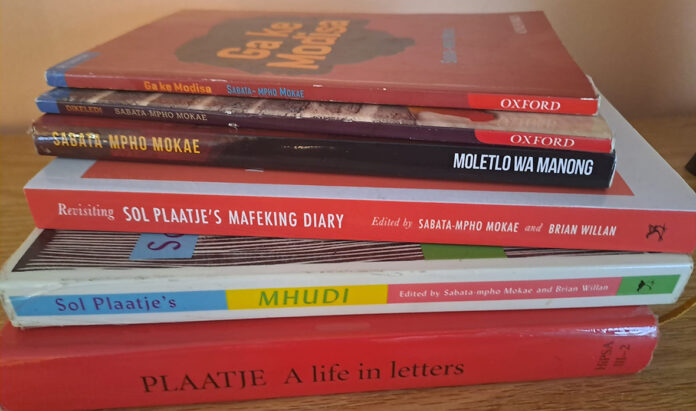

His first novel is titled Ga ke Modisa. I choose not to translate it for the benefit of Gen Z.

It came out in 2012 and, in 2013, won the M-Net Literary Award for Best Setswana Novel as well as the M-Net Film Award. It has been taught at North West University and Central University of Technology for about a decade.

“This is the same book that secured me a place as a writer-in-residence at the University of Iowa,” he reminds me.

His other works are Dikeledi, a 2014 teen novella, and Moletlo wa Manong, a sequel to Ga ke Modisa. It came out in 2018.

On Friday he’ll be launching his latest Setswana offering, Lefatshe ke la Badimo, a historical novel set in the winter of 1913 when the Natives Land Act was put into effect.

June 20 is not just a date on the calendar. It was on this Friday in 1913 that the Black man suddenly found himself landless.

Mokae once told me: “I took the decision to write in Setswana when I was a research associate at the Sol Plaatje Museum in Kimberley.

“I was exposed to Sol Plaatje’s works, and I was fascinated by the fact that whenever he wrote a book in English – Mhudi and Native Life in South Africa – he wrote a preface in which he explained why he was writing in a language other than his own.

“I got to understand that a language is not just a tool for communication among people, but it is also a way of knowing and a body of knowledge.

“This means that if we stop using our languages, we lose the knowledge carried in the phrases, idioms and proverbs in that language.

“I now know that every language is a different set of eyes through which one sees, understands and interprets the world and life.”

Need I say more?

Hleze Kunju was the first person at Rhodes University to bag a PhD written in isiXhosa.

Mokae and Kunju are the torchbearers of our literary revolution. I’m again not sure how many people have had sight of Kunju’s paper, but it should be available online.

The best that parents can do to put their shoulder to the wheel of this noble drive to reclaim our indigenous languages is to communicate in these languages with their kids.

I end here: speak as much English as you want, but remember Ngugi – put your own vernacular on an especially elevated pedestal. Robala ka Khotso Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Makatile is Sunday World Weekend Editor