Mwangala Lethbridge often pictures Zambia’s leadership spaces, cabinet rooms, boardrooms, and corporate meetings, as a table of ten seats, nine taken by men.

The image, she says, captures the architecture of exclusion. “Women are invited into leadership only in fragments,” she told bird, in an interview. “You’re expected to represent many yet supported by few.”

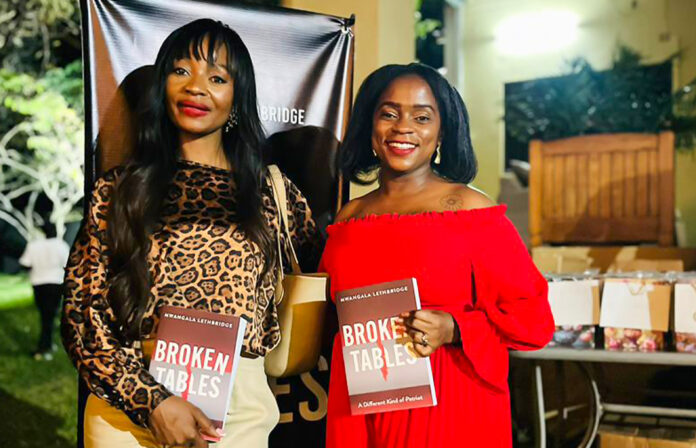

It’s this imbalance that inspired her new book, Broken Tables, a chronicle of thirty Zambian women who have carved out space in politics, business, and public life. Through their stories, Lethbridge explores what happens when women stop waiting for seats and start redesigning the table itself. An architect by training, entrepreneur and “politician in the making,” she has long examined how systems, both physical and institutional, shape power. “Architecture taught me how people use spaces,” she says. “Entrepreneurship taught me survival. Politics showed me how power works, often in corridors where women are excluded.”

Her earlier memoir, Still Standing, traced her own encounters with Zambia’s political culture. Broken Tables extends that journey outward, assembling voices of women who have navigated the same silences and found ways to speak.

Tired of begging for a seat

When asked about the book’s title, she laughs. “I got tired of begging for a seat,” she says. “You walk into a boardroom and there are ten chairs, nine for men, one for women. And even that one is to be shared among many of us. So, I said, thank you, but I’m breaking the mukwa table. Women can lead from wherever they are. You don’t need a boardroom to be a captain of industry.”

This redefinition of leadership away from titles and toward influence runs through the book. Women now hold about 24% of parliamentary seats across Africa, according to the Africa Gender Index 2023 Analytical Report released in late 2024, reflecting steady gains in political participation over the past decade. In Zambia, World Bank gender data shows women occupied roughly 15% of parliamentary positions in 2024, a reminder that national progress still trails the continental average. The numbers remain modest, but the momentum is evident.

Still, Lethbridge insists progress isn’t just statistical. “We’re good at policy,” she says. “We’re good at workshops. But we’re weak at enforcement. Until the woman in the rural area feels this progress, we’re only talking to ourselves.”

Among the women she interviewed, she saw a pattern: resilience forged through exclusion. “Every woman had faced some form of misogyny,” she explained. “They had to prove they belonged. They were told to speak, but not too loudly. It’s like being invited to the table, but told not to eat.”

That endurance, she says, often came at a cost. “One woman told me how she rose in politics but lost her relationship with her daughter. She said, ‘I shouldn’t have been made to choose between career and family.’ That broke me. Because I’ve asked myself the same question, when you’re chasing leadership, what are you leaving behind?”

New generation of women mavericks

Yet, for every story of sacrifice, there is one of defiance. “The younger women aren’t waiting to be asked,” she says, smiling. “My generation was diplomatic. Theirs is fearless. My daughter tells me, ‘Mom, you’re overthinking it.’ They just go for it.”

Her laughter fades into reflection. “But that’s growth. I was raised to be a ‘good girl.’ The next generation is raised to be free. I love that.”

Lethbridge’s own understanding of power has evolved. “When I was younger, I thought power meant being loud,” she says. “In architecture, I had to act like a man to be heard. But now I see power is quiet. It’s collaborative. It’s authentic. Power today is connection, not dominance.”

That philosophy also shapes how she treats failure. “I lost an election,” she says simply. “And I was embarrassed. But I realized, failure is not the opposite of success, it’s part of it. Too often we only show the glossy version of leadership, not the messy middle. ‘Broken Tables’ gives women permission to laugh at their failures. To know they’re not alone.”

For Judith Kafwembe, one of the women featured in the book, that message resonated deeply. A Chief of Staff to the Managing Partner at KPMG Zambia, she says being part of Broken Tables was “an eye-opener.”

“I came in thinking leadership was about politics or big titles,” she said. “But I realised it’s about impact, the everyday choices that shape people’s lives and build nations. If that’s not politics, then what is?”

Her reflections mirror Lethbridge’s belief that leadership begins where women already stand. “I think my biggest barrier was myself,” Kafwembe admitted. “For a long time, I didn’t think I had a voice. With time, through mentorship and honest conversations, I learned to believe in my own capacity. Even our internal barriers can be overcome, they’re part of the journey.”

Passing on the baton

Mentorship, she adds, has become central to how she leads. “Someone once brought light into my darkness,” she says. “Now I feel it’s my obligation to pass that light on. Sometimes people don’t even know they need mentorship until you reach out. That’s what leadership really is, seeing others before they see themselves.”

Zambia’s 2023 National Gender Policy has revitalised initiatives to increase women’s involvement in governance, enhance safeguards against gender-based violence, and boost access to finance and land. Civil society organisations such as the Non-Governmental Gender Organisations’ Coordinating Council persist in advocating for more powerful female representation in public affairs. However, as Lethbridge states, “Cultural transformation precedes policy.” “You cannot create laws for bravery.”

That courage, she says, is already visible in schools and communities. “We need to teach leadership early,” she argues. “Let girls speak. Let them lead projects. Mentorship must start in the classroom, not the boardroom.”

Her perspective on leadership, seen as a network of relationships instead of a hierarchy, positions her alongside an increasing number of African women who are reshaping power to fit their own definitions. With Rwanda’s 60% female representation in parliament and Kenya’s increase in women in gubernatorial and judicial roles, the leadership scenario across the continent is evolving.

Still, Zambia’s story feels distinct. “It’s quieter,” Lethbridge said. “We’re not just adding women to systems. We’re redesigning systems to serve humanity.”

That, she believes, is what sets ‘Broken Tables’ apart. “It’s not a book of victories,” she said. “It’s a book of becoming.”

Kafwembe agrees. “The biggest lesson for me,” she says, “is that we don’t literally need to sit at the table to make an impact. Wherever you are, in an office, a market, or a classroom, find your light and share it. That’s how change spreads.”

Lethbridge smiled when recalling one of the statements one of the women made in the book. “It’s the book’s whole message,” she said. “We’re not breaking tables out of anger. We’re building new ones, stronger, wider, and open to everyone.”

© bird story agency