Author Elias Masilela is convinced that ANC defector Glory Lefoshie Sedibe – also known as Glory September – had strong presidential qualities but ended up, instead, as what he calls “the worst askari in the liberation process”.

In a wide-ranging interview reflecting on his 2007 memoir, Number 43 Trelawney Park / KwaMagogo, Masilela revisits the liberation-era figures who passed through his family home in Manzini, Swaziland – some of whom, he says, possessed the depth, discipline and moral clarity to have led South Africa.

“I will give you more than five,” he says when asked to name those who, in his view, could have become exceptional presidents. Among them are Glory September, Kelly, Philipos Mwedamutsu, Cassius Motswaledi, Fani, John Nkadimeng,

Jabu Shoke, Humphrey Mkhwanazi, Viva Dlodlo and Nkosinathi Maseko.

But September stands out for a darker reason. “My worst prophecy was when I predicted Glory September as the future president of South Africa,” Masilela says. “He ended up the worst askari in the liberation process.”

September was abducted from Swaziland by apartheid security forces and tortured until in 1986 he turned and collaborated with the enforcers of the then government.

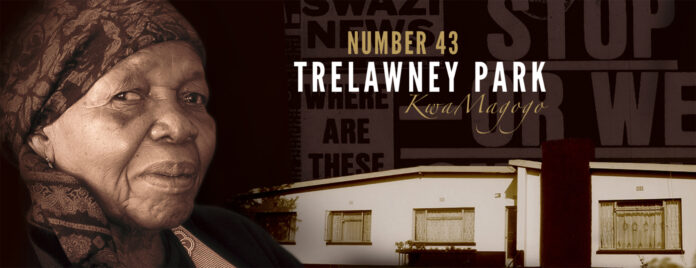

Number 43 Trelawney Park / KwaMagogo reconstructs the story of an unassuming house in Manzini that quietly became a nerve centre of the South African liberation struggle. The home, owned by Solomon Buthongo and Rebecca Makgomo Masilela – known as uMagogo – served as a clandestine safe house, transit point and operational base for members of both the ANC and the PAC in exile.

At its centre was Rebecca Masilela, the maternal anchor who fed, sheltered and steadied young cadres living with the daily risk of arrest, betrayal or assassination.

Through Masilela’s eyes as a child and young man, the memoir captures the tension and secrecy of exile life, from the fallout of the Nkomati Accord to the reverberations of the Church Street bombing. It also confronts the darker chapters of the struggle – including the September 1986 defection to the apartheid security police, a betrayal that led to arrests and deaths.

Looking back nearly two decades after publication, Masilela argues that the ANC of exile years had “amazing depth in sound servant leaders, which are lacking today.”.

“So, any could have been president,” he says of the names he lists. “But it only had to be.”

Asked what the country overlooked in those figures, the former board chairman of Multichoice points to their grounding in discipline, sacrifice and collective purpose. Unlike modern politics, he suggests, leadership was not driven by ego or spectacle. “Therein lies the difference between ego and honour,” he says. “Our leaders are driven by the former, combined with greed. uMagogo was never characterised by any of the two. She served diligently, honestly and quietly. She did not do it for popularity.”

He also reflects on former president Jacob Zuma, describing a shift in perception: “From a trusted leader and father figure to someone who leaves us with mixed feelings today.”

If he were writing the book for the first time in 2026, Masilela says he would be braver about exposing other alleged informers. “The one theme that stands out is who the other askaris were who lived at Number 43, apart from September,” he says.

There was, he reveals, “an offer on the table” to disclose more – one he refused.

“I couldn’t live with the risk of being told that it was either my parents or my siblings,” he says. “It is a truth I would never have been able to bear.”