The MK Party (MKP) has laid blame for the R350-million drug cache uncovered at an abandoned farm in Mpumalanga, squarely at the doorstep of ANC legislators, accusing them of dragging their feet on land restitution and thereby creating fertile ground for criminal syndicates.

The party’s fury follows a Hawks-led raid over the weekend that shut down an international drug laboratory at Oudehoutkloof farm in Volksrust.

Police arrested five Mexican nationals carrying questionable travel documents, along with an elderly South African man. Two other suspects – believed to be from West African countries – fled into nearby bushes and remain at large.

Authorities uncovered a chilling scene: freezers packed with crystal methamphetamine valued at about R350-million, neatly stored in lunch boxes and buckets. Surrounding the drugs were barrels of precursor chemicals, laboratory equipment, and makeshift

security in the form of a pellet gun with blanks and three live 9mm rounds.

The discovery comes just months after a similar operation was shut down in Standerton, less than 100km away, where police seized equipment, chemicals and drugs worth more than R50-million.

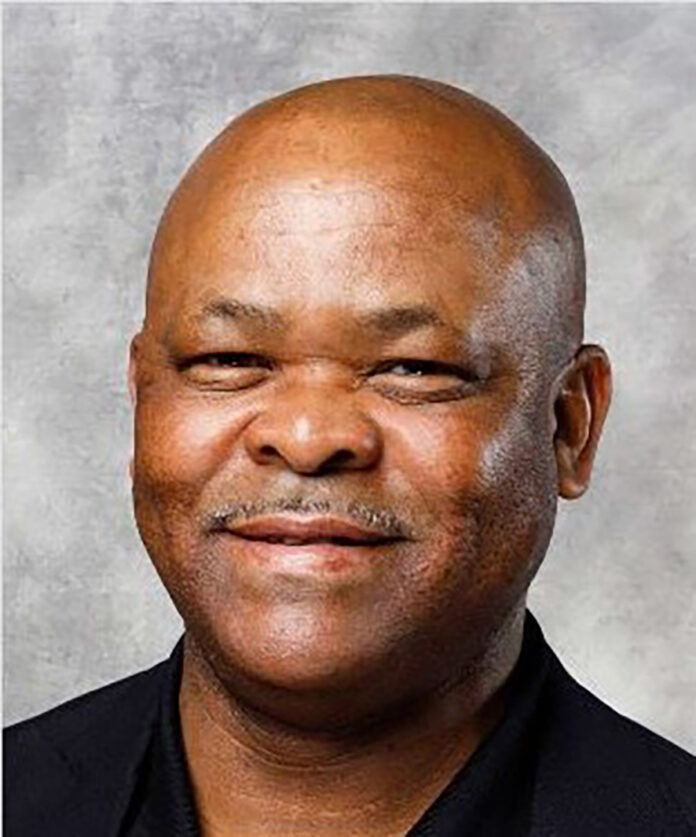

While opposition parties in the province, including the FF Plus, praised the Hawks for their decisive strike, the MKP saw the bust as a symptom of something far deeper. “This is a result of the catastrophic delays in land restitution, which leave farms idle for criminals,” said MKP legislator Pekky Shongwe.

He warned that the problem extended beyond policing. “This farm, like many others, should have long been restored to its rightful owners for productive use and not left as a haven for drug lords due to the ANC’s snail pace at land reform,” Shongwe told members of the provincial legislature during a sitting this week.

For Shongwe, the matter is historic. “Our forefathers, who fought and died for their land, are being let down by the ANC-led government. Our farms are turned into drug-manufacturing areas by foreign nationals.”

His words echo the findings of parliament’s own watchdog.

In its most recent oversight report tabled on January 28, the portfolio committee on land reform and rural development confirmed the scale of the delays. It noted that “a total of 6 637 land claims had been lodged in Mpumalanga by 31 December 1998,” but that only 3 380 had been settled.

Of those settled claims, 2 122 were rural and 1 258 urban, benefiting 62 386 households and 330 768 beneficiaries, including 21 188 female-headed households and 58 persons with disabilities.

The report also revealed that 1 583 old order claims were still outstanding, while an additional 10 849 new claims were lodged between 2014 and 2016.

The scale of land acquisition is equally stark: restitution in Mpumalanga alone required 558 247 hectares at a cost of R8.7-billion.

The committee warned that to clear the backlog of old claims in the province, the Mpumalanga Regional Land Claims Commission would need about R40-billion over the next five years, a “conservative estimate”, given rising land prices.

Critics such as Shongwe said these unresolved claims and idle tracts of land create vulnerabilities. The Constitutional Court itself, in the landmark Land Access Movement of South Africa judgment, interdicted the commission from processing new claims until old ones were finalised, further compounding the logjam.

Shongwe argued that the consequence is visible in Volksrust. “There are systematic failures that allow crime to flourish that need to be addressed,” he said.

He pointed to the Standerton raid earlier this year, where drugs worth R50-million were seized, as evidence of a growing pattern. He also recalled the case in Masoyi outside Hazyview, where 95 Libyan nationals were arrested and later deported after police discovered a so-called military camp on abandoned land.

“As uMkhonto weSizwe, we will fight to reclaim the dignity and sovereignty of our people,” Shongwe said.