South Africa’s energy transition gained a significant boost this week after the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) approved a landmark strategy on natural gas.

The decision, announced on November 27, signals a major investment push into gas infrastructure, power generation, industrial supply, and regional cooperation at a time when South Africa faces both an energy security crisis and a looming “gas supply cliff”.

The PIC says the strategy aligns with the National Development Plan 2030, the Gas Masterplan, and the Integrated Resource Plan 2025.

It allows the state-owned asset manager to invest both directly and indirectly in midstream and downstream gas projects, assessed on a risk-adjusted basis.

At its core, the strategy aims to stabilise the energy system while creating space for renewables to scale, arguing that gas offers the flexibility and dispatchability South Africa currently lacks.

Five pillars of the plan

The plan is built around five pillars, each critical to economic and industrial stability.

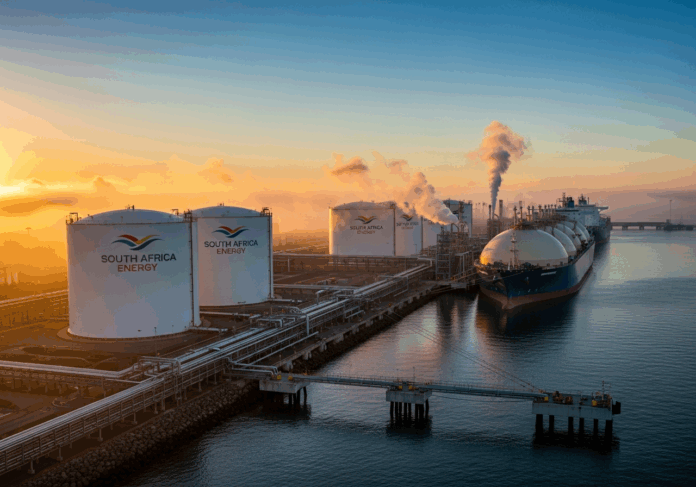

The first is gas infrastructure investment, from pipelines to LNG import terminals, which the PIC describes as foundational to developing a functioning gas market.

The second focuses on converting existing open-cycle gas turbines at Ankerlig and Gourikwa from diesel to gas, while also supporting a proposed 3 000MW gas-to-power plant in Richards Bay, a project considered central to stabilising the grid.

A third and urgent component is the need to avert South Africa’s industrial gas supply cliff.

Several large manufacturers, chemical producers, and mining-linked industries rely heavily on gas as feedstock or fuel, while many face supply disruptions as legacy contracts and sources decline.

The PIC warns that failure to secure a new supply could impact thousands of jobs and weaken key sectors of the economy.

The fourth pillar highlights regional cooperation with gas-rich neighbours such as Mozambique and Namibia.

Downstream investment opportunities

Cross-border collaboration is essential, the PIC says, not only to secure supply but also to position Southern Africa as an integrated gas and industrial hub.

The final pillar expands gas use beyond power generation into the chemicals and fuels value chain, including ammonia, urea, methanol, and synthetic diesel.

For sectors like agriculture and mining, this could support improved reliability and new downstream investment opportunities.

Proponents argue that natural gas could cut emissions relative to diesel and coal while enabling greater uptake of renewables by providing flexible backup power.

The PIC notes that gas-to-power infrastructure can “unlock broader opportunities for developing renewable energy”, particularly when combined with storage and grid modernisation.

However, South Africa remains without a guaranteed long-term gas supply, making infrastructure investments vulnerable if LNG import plans stall or regional deals falter.

Policy uncertainty

Environmental groups warn that expanded gas infrastructure could lock the country into fossil fuel use for decades, complicating its long-term decarbonisation trajectory under the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan.

Policy uncertainty, including slow licensing turnaround times, adds an additional layer of challenges.

Yet the PIC’s move marks one of the strongest institutional signals to date that South Africa views gas as a necessary transition fuel rather than a permanent solution.

If executed effectively, the strategy could reduce load-shedding risk, stabilise the industry, and buy the country time to scale renewables.

If delays mount, the risk of stranded assets or prolonged dependence on imported fuels becomes hard to ignore.