The Special Investigating Unit (SIU) has reported its most financially consequential year to date, claiming to have recovered and prevented corrupt officials and associates from stealing a total of R4-billion from state funds in 2025.

The figure, announced in its annual review released on Monday, provides a quantifiable measure of progress in the protracted fight against state graft, even as the unit navigates profound systemic challenges and escalating political scrutiny.

The SIU’s financial tally for the year consists of R1.3-bn in direct cash and asset recoveries— more than double its internal target —and a further R2.7-bn in potential losses prevented through court interdicts.

Perhaps more significantly, the unit secured court orders to set aside contracts and administrative decisions valued at R5.6-billion. This while preparing evidence for civil claims worth an additional R12.1-bn. These outcomes, largely driven by the specialised Special Tribunal, represent a shift from merely exposing corruption to enforcing material consequences.

High profile cases

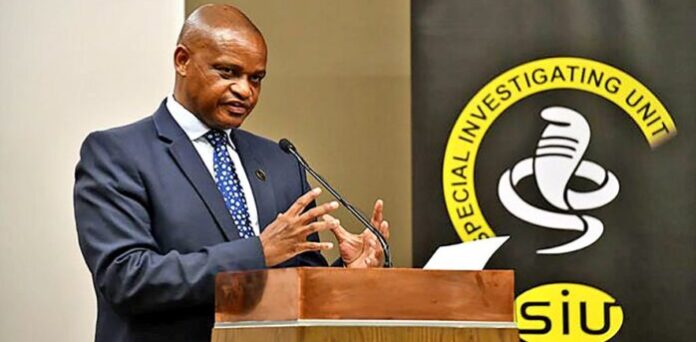

“The judiciary’s validation of our work reinforces the principle that corruption has consequences,” said Advocate Andy Mothibi, the unit’s head. “Each ruling strengthens the foundation for systemic reform. And it sends a clear message that maladministration will not go unchecked.”

The year’s work was defined by several high-stakes cases. These targeted provincial governments, state-owned enterprises, and the intricate networks that surround them.

In a landmark ruling underscoring the personal liability of governance failures, the Johannesburg High Court ordered three former SABC board members to personally refund R11.5-million unlawfully paid to the broadcaster’s former chief operating officer, Hlaudi Motsoeneng.

Similarly, the Special Tribunal directed the KwaZulu-Natal MEC for Education to discipline 16 officials involved in awarding a R2.5-million chemical toilet contract without any competitive process, a violation of constitutional procurement rules.

The service provider was ordered to repay all profits. In Limpopo, the tribunal preserved R816-million in luxury assets. These included vehicles, art, and cryptocurrency — all linked to businessman Morgan Maumela. The latter is implicated in the scandal-plagued Tembisa Hospital contracts.

Following the money trail

These cases illustrate the SIU’s operational focus: following the money trail to its endpoint. And whether that leads to a boardroom or a luxury estate. The unit also froze R2.7-million from the sale of a property linked to a National Lotteries Commission scandal, where R230m in community grants were allegedly diverted to buy private homes in affluent estates.

Beyond individual cases, the unit’s expanding mandate signals political acknowledgement of the problem’s scale. President Cyril Ramaphosa signed 26 new proclamations in 2025. This authorised investigations into entities including Eskom, Transnet, the National Skills Fund, and South African Tourism. And this widening net grants the SIU formal jurisdiction, but also burdens it with monumental expectations.

To manage this, the unit has increasingly turned to technological tools. Its investment in data analytics has begun to pay forensic dividends. It uses predictive modelling and network analysis to detect fraud patterns.

Mothibi notes that this modernises the investigative approach.

Leveraging on G20, new technologies

“Data-driven insights now inform key decision-making processes,” he said. “[It is] helping investigators prioritise high-impact leads and enables early identification of systemic weaknesses.”

Concurrently, the SIU has sought to bolster its international posture. Under Mothibi’s guidance, South Africa has used its 2025 chairmanship of the G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group to advocate for stronger asset recovery protocols and whistleblower protections.

The unit has also signed cooperation agreements with agencies in jurisdictions including the United Arab Emirates, Mauritius, Kenya, and Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption, recognising the cross-border nature of illicit financial flows.

However, the record recoveries exist within a wider landscape of persistent dysfunction. The SIU’s successes often spotlight the very institutional failures they seek to correct. Municipalities that bypass procurement law, state boards that disregard financial controls, and the departments that lack basic oversight.

Each R1-billion recovered is a tacit indictment of systems that allowed the theft to occur. Furthermore, the unit’s dependence on presidential proclamations to initiate investigations invites criticism about potential political influence over its agenda.

Broader institutional reform

The true test of the SIU’s impact lies beyond annual financial metrics. It rests on whether its work deters future corruption and catalyses lasting institutional reform within the state bodies it investigates.

While the R4-billion figure is a powerful symbol of enforcement, South Africa’s National Development Plan estimates a far starker reality. The country may lose as much as

R47-billion annually to corruption, suggesting the battle is far from won.

The SIU’s 2025 report ultimately presents a duality. It is a narrative of a specialised agency hitting its operational stride. It is deploying legal and technological tools with increasing effect under Mothibi’s steady leadership.

Yet, it is also a reminder that these commendable efforts are a containment exercise against a deep-seated crisis of governance. The unit’s success is measured not just in rands recovered. It is measured in the integrity it helps salvage from a system still under profound strain.