Government and Justice

When do we imagine the pain of injustice South Africans will end, from apartheid to democracy – and then in the intervening period of slightly under 30 years we are back to an unjust epoch of another kind, not dissimilar to the previous period black people endured during the oppression and injustice we thought we had escaped?

The apartheid and colonialism eras represented the darkest moment in the history of this country. Black people were singled out for oppression and denial

of opportunities such as a good education and participation in the mainstream economy.

The foreigners came to our country and took charge of the endowments inherited from nature – fertile soil, mineral sources, ocean economy – denied us the opportunity to excellence and achievement; gave us inferior education; closed the doors of commerce and industry to us; and did everything that keeps a good man or woman down.

What does the Easter moment tell us today about everything bad and ugly we have ingested over 300 years of our dispossession and marginalisation?

More than 370 years of darkness has pervaded the political air of South Africa since the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck. The pungent political air was also permeated by the arrival of British settlers in the 19th century during which the marginalisation took place, stripping indigenous people of their rightful ownership of the land.

Embedded in the Easter moment is the day referred to as Good Friday. It was the moment of crucifixion of the one who objected to imperialistic tendency of the Roman rule, and the Romanisation of his land by foreign forces. He went to the cross, as the leader of the Jesus Movement to fight an injustice heaped upon his Palestinian community by the imperial forces.

His name, for more than 2 000 years, has been elevated, and metaphorically referred to as having been resurrected from the death.

Today in South Africa and other parts of the world we celebrate his resurrection. His action of fighting injustice has enlightened the world to seek light and justice and human rights.

The question for the modern-day South African who celebrate the event is: what might this period signify if it is stripped of its religious connotations?

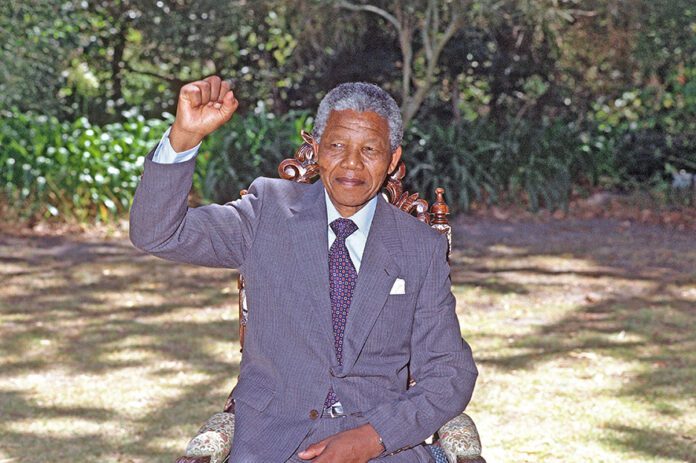

The year of Nelson Mandela, 1994, marked by the long and winding queues at every corner of our country, was significant in many ways. Men and women of different ideology joined the queues to honour the man of great character – to vote for his party because he embodied the

ideals many could relate to – ideals of justice and democracy and equality.

Recently former president Kgalema Motlanthe attended a ceremony held in Richards Bay, KwaZulu-Natal, in honour of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi. The KwaZulu-Natal ANC chapter historically is vehemently opposed to Buthelezi’s politics. Historically, he has been roundly condemned by it and described in the past during the internecine wars of attrition involving the IFP and ANC as “a sell-out”.

This is what Motlanthe said of Buthelezi in his honour: “You stood side by side with fellow freedom fighters. We owe your generation a debt.”

But how should we perceive politics as the art of the possible, to steal from the words of German theorists Otto von Bismarck – a stateman who played a significant role in the unification of Germany process?

Politics is also about pragmatism that helps to resolve difficult political issues.

But I digress. The central point to make is to suggest that millions of South Africans who went, for the first time, to cast their vote in 1994, were full of hope that light had eventually come to their troubled country – a period in which the country was engulfed in the darkness for the past 300 years of oppression, imperialism, and apartheid.

Follow @SundayWorldZA on Twitter and @sundayworldza on Instagram, or like our Facebook Page, Sunday World, by clicking here for the latest breaking news in South Africa.