If you meet any ordinary person in the streets – a working class or a poor villager – and you ask them how does it feel to be a South African, they will, without hesitation, tell you “things for us do not look too good”.

If you press them hard enough for further commentary, they might, after a shrug of shoulders, and with a heavy sigh, look you in the eye and say, “where is that country of milk and honey promised by Nelson Madiba?”

They will walk away with a heavy heart into their uncertain world, wondering what the future might hold and cursing the ANC administration for turning their country into a wasteland through many acts of corruption ventilated by the Zondo commission.

They will sorrowfully ask, “is it possible for our Madiba to come out of his grave to redirect his glorious organisation into glorious paths”?

Some will ask, “why in the neighbouring Lesotho are folks there not experiencing loadshedding problems, yet we as the most resourceful country in Africa, with a bigger economy by far, suffer the indignity of staying in the dark for longer periods due to loadshedding”?

The irony is that South Africa exports electricity to various African countries, including Lesotho, Eswatini, Namibia and Botswana, and these countries hardly experience loadshedding.

Loadshedding exacerbates the country’s already deep socio-economic challenges – and imbalances.

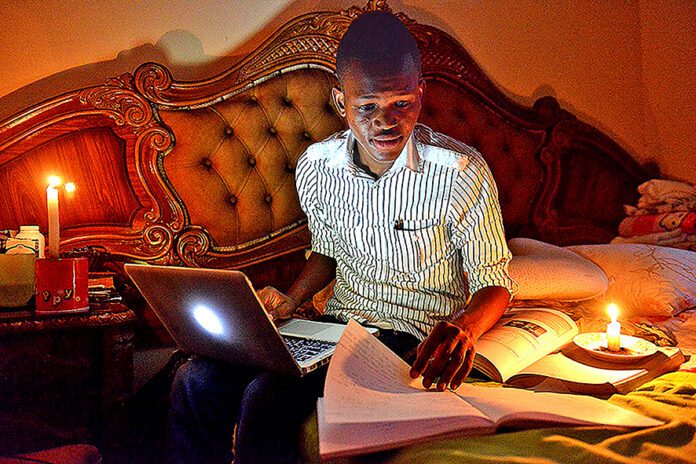

While wealthier communities, such as white people, have the economic muscle to cushion themselves against devastating loadshedding blows – with the ability to harness electricity through solar energy, generators, and other such contraptions – the same cannot be said of black communities, most of whom live in abject poverty.

As regular bouts of blackouts continue to ravage the country, black townships and villages feel the squeeze more – prone to being victims of violence, muggings and having their homes attacked more easily than white households.

As loadshedding takes its toll, the Madiba promise of a better life is not a lived reality for many black South Africans. The National Party, under the white regime, committed to addressing the “white question of poverty”, and developed mechanisms to improve the lot of many poor white people.

The ANC-led government has not done so, in the main. Millions of black people continue to languish in poverty, and many live in informal settlements.

What has become of the “better life” promise, spearheaded by comrades under the banner of the ANC government?

Whatever encouraging words said by Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana during the presentation of his budget speech this past week, black people remain on the periphery of the economic landscape.

Millions of black graduates remain unemployed as are school leavers who face a bleak future. Again, loadshedding is not making life easier for all South Africans. It stunts economic growth at all levels.

Prospective investors think twice before committing investments, a lifeblood for job creation in a country where loadshedding has become a way of life.

The clarion call by most South Africans today is that the government must find a way to end the scourge of blackouts, and help Eskom find its footing.

South Africans are waiting for light and better leadership.

- Mdhlela is a freelance journalist, an Anglican priest, ex-trade unionist and former publishing editor of the SA Human Rights Commission publications