Earlier this month, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi announced that South Africa will get R2-billion of bridging funds from the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to run until the end of March next year, which Cabinet said would “ensure uninterrupted HIV service delivery”.

It’s about a quarter of South Africa’s FY2024/5 PEPFAR grant via the (former) United States Agency for International Development, USAID, and the Centres for Diseases Control (before the USAID arm was ended in February) and is part of a phase-out plan in which “Washington is changing its approach to PEPFAR”.

But the abrupt throttle on US aid has changed the international donor funding landscape all round, with many other organisations also reducing or shifting their spends.

For example, the Global Fund for HIV, TB and Malaria, whose past contributions to HIV programmes in South Africa worked out to roughly a third of the yearly amount from PEPFAR, will now give about R2.3-billion less (calculated at current exchange rates) over the next three years (until March 2028) than was originally expected because many wealthy governments have reduced their contributions to the fund.

Over the past 25 years, international funding has played a big role in the roll-out of the country’s HIV plan — especially for research where US-backed money helped to finance large national surveys to track what the picture of HIV in SA really looks like, and especially at the height of AIDS denialism.

For example, 30 years’ data shows how HIV prevalence — the proportion of people who have HIV at a given time — quickly rose among pregnant women between 1990 and 2005, plateauing around 30% for the next decade and going down slightly by 2022, the most recent year the survey was run.

Today, South Africa has the biggest HIV treatment programme in the world, with about 6-million people on antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) and a finelyw orked out data set that tracks HIV statistics in the country that helps to inform policy decisions.

Although taxpayer money now funds the bulk of South Africa’s HIV programme, getting to this point would not have been possible without donor support.

In fact, since its start, PEPFAR has spent about $8-billion (R140-billion at the current exchange rate) in the country, and projections show that if PEPFAR funding stops without being replaced by government money, between 150 000 and 296 000 additional new HIV infections and between 56 000 and 65 000 HIV-linked deaths are likely by 2028.

On top of this, many of the health workers and data capturers employed by PEPFAR-funded NGOs will be without a job.

The reality is that the golden age of health development assistance is over. But can there be opportunity in adversity?

Rethink business as usual

National statistics show that HIV caused 169 076 deaths in 2010. Fifteen years later the number sits at 77 639.

Although this is a 54% drop, it’s still far from UNAids target of getting deaths down to only 10% of what the figures were in 2010 — in other words, 16 907 — by 2030.

Moreover, life expectancy has climbed from around 57 to 67 years in the last decade and about a fifth of the population is older than 50.

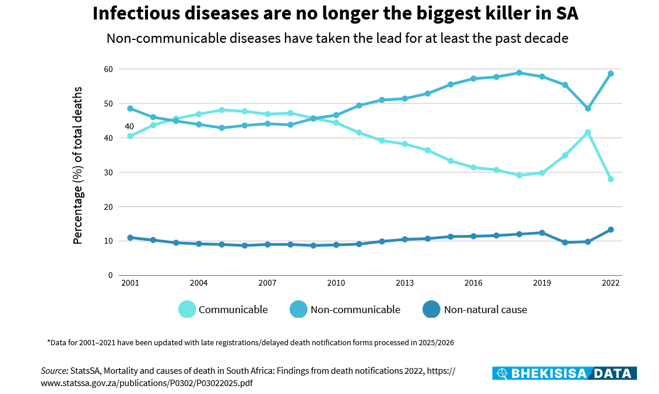

However, deaths from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, heart conditions, and obesity now far outweigh those from infectious diseases, with the crossover seen in 2009, around the time when access to ARVs was expanded hugely by allowing nurses, as part of primary healthcare, to start people on antiretroviral treatment.

The changing picture of South Africans’ health — an increasing burden of NCDs amidst continuing high rates of HIV infection and an aging population — means that the country, like many others that rely on financial help, will need to rethink how it responds to HIV within the context of declining donor funding.

An immediate reaction, especially by those who have worked in the HIV field for decades, is to protect and increase funding for the programme.

This means increasing the health budget and channelling the extra money to HIV projects so that the work relying on PEPFAR support previously can continue, whether through NGOs or in the public health sector.

Assuming that this was possible from a fiscal point of view, this option is appealing, as it would mean that services can carry on with no or very little disruption — especially those for groups of people with a higher chance of getting HIV than the general population (key populations) such as sex workers, gay and bisexual men, and transgender people.

Moreover, should the government decide to continue to use NGOs to provide HIV services, the thousands of health workers employed by these groups will keep their jobs.

But there are downsides to this.

To start with, services that were “nice-to-have” or run inefficiently will carry on as before, and the chance to review — and revise — what works and what doesn’t will be lost.

But more than that: the country won’t be able to use the lessons from the HIV programme to strengthen primary healthcare — the cornerstone of universal health coverage (UHC)

South Africa’s approach to UHC is called national health insurance (NHI), which will work like a big state-run medical scheme that will pay for everyone’s healthcare. The fund will decide which services will be included and how providers will be paid.

As some HIV services will form part of the primary healthcare package, this implies that the funding available through the conditional grant could be folded into the NHI.

Do more with less

A different way of thinking could be that South Africa uses the current situation to take seriously that HIV is a chronic disease and integrate its management into primary healthcare.

For example, research shows that people older than 50 who are on ARVs may be up to four times more likely to have another chronic condition such as high blood pressure or diabetes, and with South Africa’s ageing HIV population, offering services for primary health issues and HIV together can be a smart plan.

What could a more integrated approach to HIV services look like then?

One solution could be to make HIV services part of those offered at places where pregnant women go for routine health checks, mothers take their young children for vaccinations or people get sexual and reproductive health advice — especially with lenacapavir being planned to start rolling out at some clinics from February.

Making HIV treatment and prevention services available at these facilities can help not only to end mother-to-child transmission but also to markedly lower infections among teenage girls, based on data presented at the health department’’s lenacapavir roundtable meeting earlier this month showing that 114 000 girls between 15 and 19 gave birth in the public sector in 2024.

Linked to this is to move away from a rigid, one-size-fits-all plan for healthcare, and rather adapt services to the needs of specific client groups — as has been done in differentated care for HIV.

Building these lessons means, for example, that patients whose conditions are well under control can get several months’ medicine in one pick-up and through the centralised chronic medicine dispensing and distribution system.

Using data from this system can help to flag when people are not taking their medication consistently, and by using artificial intelligence, such data can be turned into meaningful information to make programmes run more efficiently, understand people’s preferences for health services better, and empower them to take charge of their own care.

Lastly, incorporating HIV data systems into those for primary healthcare and at the same time using the experience of keeping track of HIV patient information for follow-up and keeping people in care, the system can be improved all round. This can include making HIV surveys part of the country’s general health surveys.

The most bang for limited bucks

But there is also a need to tread with caution, so that people who come for HIV prevention or treatment aren’t left worse off than they are now, even with reduced funding.

For example, ill-considered integration of services when resources are spread too thin could lead to clinic staff being overworked, longer waiting times, and a drop in the quality of care.

People could also feel that they will be discriminated against at facilities that offer different services, which could erode their trust in the health system or fuel stigma — especially for key populations.

Many donors, including the Global Fund and PEPFAR, fund standalone programmes and need solid data to report on the impact of how their money is spent.

When HIV services are bundled into primary care, it’s possible that getting such HIV-specific data could be compromised and so make remaining donors reluctant to continue with their funding.

But this can be overcome, and it’s possible to get donors on board to buy into the idea of strengthening both primary healthcare and HIV services. For example, donor funding could be provided directly to government institutions rather than to NGOs.

This is the case in Zambia, where the number of people started on HIV treatment increased by 31% between 2014 and 2019 and viral load coverage rose from 73% to 88%.

In short, rethinking how to handle dwindling international aid to South Africa could benefit not only the country’s HIV response but also programmes that have to deal with the surging burden of NCDs — and so help to make healthcare more accessible and equitable all round.

This story was first published by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Yogan Pillay heads up HIV and TB delivery at the Gates Foundation. Bhekisisa receives funding from the Foundation but operates editorially independently. Read more about our founding policies.

![]()